By Sarah Al-Arshani

At 18 years old Vidya Sri was happily in a relationship with her boyfriend Billy, until her dad found out. Sri was then sent to India, a country she had only been to briefly and told that she could not come back without a husband. She married and came back to work in a bank eventually making her way through the ranks and gaining the financial independence to leave the marriage.

“And it went from feeling like I had this wonderful boyfriend to an incredible amount of violence and trauma,” Sri said.

After leaving, Sri called women’s organizations to see if she can connect to women who had also been forced to marry.

“I felt very alone. I knew there must be so many other women like me and I was determined to find them.” Sri said

She was met with frustrating replies stating that “forced marriages” don’t exist in the United States. She later founded Gangashakti, an organization dedicated to research and awareness on forced marriage.

“Everybody said to me no no no you didn’t have a forced marriage, you had an arranged marriage. There’s no forced marriage here in the the United States,” Sri said. “So that really you know pissed me if for lack of a better expression.”

Sprawled up on her couch at the age of 30, Lisa Shannon recalls watching a segment on Oprah in 2005. She talked about the mass rape of women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during its war. Shannon was so moved by what she saw she started Run for Congo Women, and over the course of five years raised more than $17,000,000 for Congolese women.

“I was quite shocked that I had never even heard of the war happening there, Deadliest war since World War II. And decided to just do what I could which at the time was just run and raise money for women in the Congo,” Shannon said.

She later went on to co-found Sister Somalia, the first sexual violence crisis center for women in Mogadishu, Somalia. She started campaigns centered on addressing issues of violence against women.

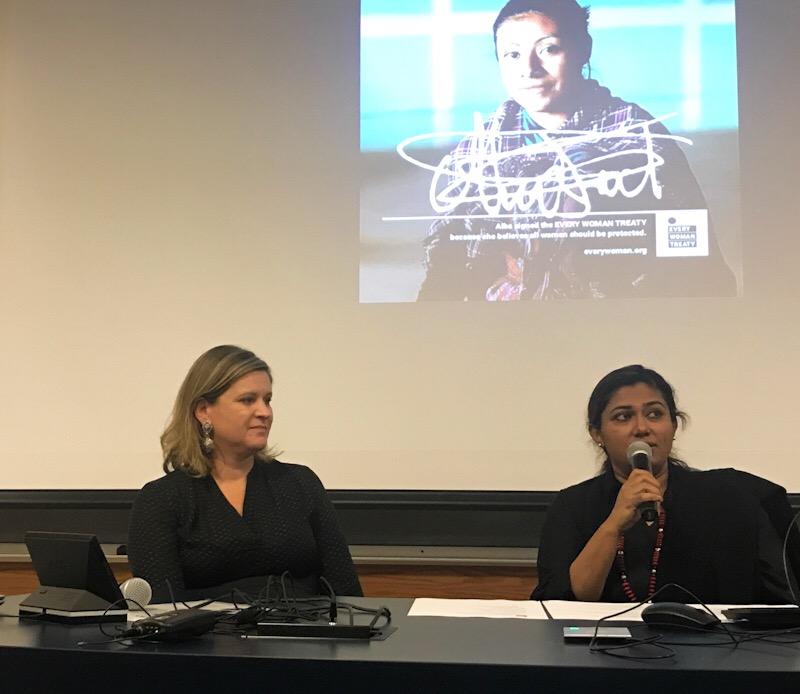

Lisa Shannon (Left) and Vidya Sri (Right) co-founded Everywoman Treaty and organization working to enact an international treaty to address violence against women. The two discussed their work during a speech at the University of Connecticut on December 3. (Photo by Sarah Al-Arshani)

Shannon met Sri in 2013 at the Carr Center at the Harvard Kennedy School where they were both Human Rights Policy Fellows. The two, with the help of activists Charles Clements, began to work to create a treaty to end violence against women.

Sri and Shannon discussed their work with Every Woman Treaty, formerly Every Woman Everywhere, in a speech entitled Mobilizing the World to End Violence Against Women: The Campaign for an International Treaty, to a group of more than 50 students on Monday December 3. The speech was organized by the UConn Humans Rights Institute .

The treaty which they hope to release in February 2019 is modelled after the Tobacco and Landmine Treaties. It’s meant to be a hard set of goals that a country either did or did not. Sri said it was important this be a measurable goal and not just a recommendation that a country address an issue.

Sri used the analogy of when everyone was allowed to smoke virtually anywhere, and now there are regulations around where smoking is allowed due to the Tobacco Treaty.

More than 50 University of Connecticut students listened at human rights activists Lisa Shannon and Vidya Sri explained their work with Everywoman Treaty and their efforts to see a treaty addressing violence against women. (Photo by Sarah Al-Arshani)

Despite push back or claims that a treaty is not needed, the pair are adamant that a cohesive agreement to tackle violence against women is needed to solve the problem.

They said that existing laws and treaties, specifically the Convention on All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) allow for gaps in tackling violence. Shannon said that CEDAW does not even utilize the term violence in addressing discrimination against women.

There are also gaps in addressing this issue from country to country. Shannon personally recalled an experience in Somalia in 2013 where a woman was arrested for allegedly making a false accusation that she was raped by security forces.

The woman was given a finger test, to see if she had been raped, and the incident sent shock waves through the community. Women who Shannon had worked with refused to speak to her, other activists or even each other in fear they could be arrested. Eventually, Shannon said an international petition called for the woman’s release.

“But you do end up thinking what about all the women who don’t get 700,000 signatures. There’s something wrong here because foreign ministers could not really say ‘you are violating an international standard. All they could say is tisk tisk you really ought not act that way,” Shannon said “but there is no international standard around this.”

Their proposed treaty would eliminate those gaps, according to Sri and Shannon.

It’s reported that one in three women will face domestic or sexual violence, but Shannon said that all women will face or know someone who faced some form of violence.

Sri said that after meeting Shannon and looking into the gaps of policies against violence against women internationally, she was able to understand why she was forced into marriage.

“It really helps me understand what I just went through. So I was not an accident. There’s a reason why I went through what I did,” Sri said.