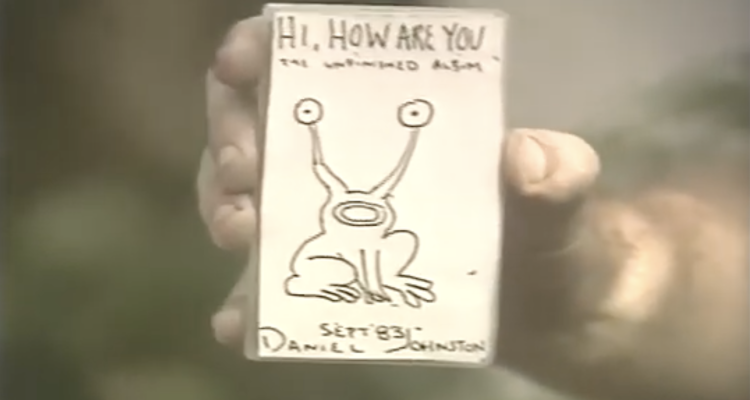

Imagine, for a moment, it’s fall of 1983 and you’re standing on a street corner in Austin, Texas. You might be listening to Speaking in Tongues by the Talking Heads, Synchronicity by The Police, or Madonna’s eponymous debut. A stranger with bushy eyebrows wearing a McDonald’s uniform approaches you, hands you a cassette decorated with hand drawn marker art, and informs you matter of factly that he is going to be famous someday.

You’d do well to bet on him. This record, filled with plodding chords and creaky vocals, would write Daniel Johnston into the music history books. Hi, How Are You is a seminal record in the weird world of outsider music, a niche subgenre where people relegated to the sidelines of society ostensibly get a voice. Forty years later, the shockingly original music of Johnston – and the narrative that props it up – retain relevance in talking about both what we listen to and how we listen to it.

Johnston’s music, like other outsider music, asks a lot of the listener. To enjoy it, you have to check your expectations of how music should sound at the door. In return, the outsider musician invites you into a raw, inventive world full of heart and compassion. But designating an album as outsider music comes with some baggage. At forty years, this album deserves a relisten at Daniel Johnston’s level, not above it.

Hi, How Are You is a little universe. In sparse, often haunting songs, Johnston weaves in humor and recurring characters, like Joe the Boxer. He recorded it in September 1983 after being kicked out of his brother’s house and moving to Austin, TX. Sometimes Johnston wouldn’t be able to copy the cassette and he’d record the entire record front to back again.

Johnston’s cassettes were just that – cassettes. Johnston’s muddled tracks have the warm hum of a boombox recording. The album carries a certain familiarity. Daniel Johnston sings the tuneless song you hum when you’re alone. Some of his most memorable tracks are those where he sings a capella, like the opener ‘Poor You’, which describes an angel who comes down and validates the singer’s pain.

Johnston’s instrument of choice is most often a chord organ. On ‘Desperate Man Blues’, Johnston sings over a sample of a slowed down jazz track. The instrument used on tracks like ‘I Am a Baby (In My Universe)” and “Nervous Love” was likely a toy Smurf ukulele. It’s worth saying here that Johnston’s music sometimes just isn’t good, at least not in any conventional sense. Johnston’s work has a lot to offer, but not in the way the Talking Heads or Madonna has a lot to offer. To quote-unquote ‘get’ the album, you pretty much have to start with the assumption that this isn’t some casual listen.

Hi, How Are You was shorter and more musically complex than his typical hour-long albums, in part because Johnston recorded it in the middle of a nervous breakdown. Johnston struggled with his mental health for the duration of his life. He had what he described as manic depression, as well as symptoms of schizophrenia. The emotional tumult of this time undergirds songs like ‘Despair Came Knocking’, where Johnston lets despair in to stay for a while.

The core of Johnston’s music is his whole, authentic self, which can appear to be bursting open with pain. But his art is strung through with hope as well. Then there are the songs that straddle the two, like ‘Walking The Cow’. This song is a standout on the album as well in Johnston’s discography as a whole. Johnston’s thin voice and wistful melody on the chord organ create a surreal and stirring track. For many fans, this would be what hooked them on his work.

There are a lot of artists who credit Johnston with influencing their work, from Sonic Youth to Beabadoobee. Given the lo-fi quality of his work and that he self-recorded and released a lot of his music, Johnston would be credited with his influence on bedroom pop. This album predates other 60s-inspired indie like Neutral Milk Hotel and dreary lo-fi like the Microphones by at least a decade.

Hi, How Are You would become the quintessential Johnston album. After he moved to Austin, Johnston stood on a street corner handing out the tapes decorated with a marker drawing of ‘Jeremiah the Frog of Innosense’, a character of his own invention which would become representative of Johnston. In 1985 – a little under two years after he’d wrote and recorded the album – he got onto MTV to tell everyone about it. Johnston showing everyone this weird little record on national television would allow him to break out of the Austin scene.

Beyond the music, though, the album would come to be recognized for the personality that created it. This album would also be remembered as a classic of ‘outsider music’, a genre defined less by sound and more by story. The narrative of outsider music often goes like this: a lonely, often troubled person teaches themselves how to make music. In their bedroom, or their garage, or their room in the psych ward, the person writes prolifically, self publishing music that’s pretty hard to listen to which languishes in obscurity until some listener picks it up and recognizes the hidden genius inside. The hallmark of the music is what is often described as a sort of naivete. Or to rephrase, outsider music is music where the audience presumes to understand what’s happening in the work better than the artist.

Johnston wrote his preceding album, Yip/Jump Music, in a garage before being kicked out. He would later float in and out of psych wards. The form of his music also evokes childishness: the simplistic songs, the high pitched voice, the use of toy instruments. His music strikes to the heart of experience with mental illness, but it also honors the world he created for himself as entirely true. These elements are what make his music singular, but also flatten his personal narrative against his art.

This has led to fan attention toward Johnston’s life that can border on voyeuristic. Johnston’s life was full of lurid details and jarring stories of how his illness impacted those around him (including several near death experiences). This was cataloged in ‘The Devil and Daniel Johnston’, a 2005 documentary named for his well-documented obsession with Satan and other religious imagery. These stories are bolstered by Johnston’s own recordings which discuss the larger than life characterizations of good and evil which haunted his work.

It’s obviously not uncommon for an artist’s story to precede their work in one way or another. Take the example of Kurt Cobain, who would launch Johnston to further notoriety by frequently wearing a shirt with the album art from Hi, How Are You. It’s difficult to come to Cobain’s music without the baggage of his personal life. But for Johnston, his life story – to whatever degree we understand it – feels inextricable from his work. Even the title of the album has a little mythos behind it: he would approach people on the street with the cassette saying, “Hi, how are you, I’m Daniel Johnston and I’m going to be famous”.

‘Outsider music’ is a term borrowed from the art world, where ‘outsider art’ – sometimes called ‘art brut’ – became a touchstone for famous artists. The difference in the art world is that outsider artists often were truly cut off from the insular world of art. Johnston, on the other hand, was not. Johnston, who certainly was in conversation with the outside world – he just had a rich, troubled interior world as well. He played live shows; he went on MTV; he made music with his idols.

Perhaps given his aspirations toward fame, he was also not shy of the press, which allowed for fans to follow intimate details of Johnston’s life and struggles. Under the guise of capturing a truly singular (and maybe singularly tortured) artistic mind, interviewers indulged Johnston’s delusions – sometimes while he was literally institutionalized. The discomfort of these pieces is that there are moments where journalists ask about Johnston’s beliefs from a distance, while it’s clear he’s in the throes of a psychotic disorder.

Johnston wrestled with his illness, he made art about it, and his audience followed both with rapt curiosity. Forty years after he wrote and recorded Hi, How Are You, we know that Johnston was very aware of the narrative fitted to his work, and that it influenced what he created. He apparently wrote a track called ‘Daniel the Idiot Savant Rockstar’. As he told Pitchfork in 2006, “No matter what people might say, my records are pretty amateurish.” The adjectives draped onto Johnston – brilliant, autodidactic, tragic – weighed on his music and shaped the work.

Johnston’s album was rocketed forward by his ethos as an artist whose brilliance rose out of his own ignorance. That’s the kernel of what makes outsider music successful. Now more than ever, it feels like we’re all looking backwards over our shoulders to peek at who’s watching us. The idea of outsider music is that these artists never did that. Except for when they did – like with Johnston.

Right now, we want so much information about everyone all the time. From musicians we demand the early uncut demos, the gruesome childhood, the wounding first love. These morsels of a person’s life are surfaced in service of a reconstruction of their being to explain their art. But artists don’t live in a vacuum, nor do the stories we create about them. As we increasingly demand more of the personal lives of the artists we love, there’s something to be gleaned from Johnston: the more we learn, the less we know.

In that first MTV appearance in 1985, after showing off Hi, How Are You, Johnston sings ‘I Live In My Broken Dreams’, a song that’s actually not on the album owing to Johnston’s prolific output. As the camera comes in tight to his face, he looks nervous and sweaty. He begins in his high quaver: “When I was out in San Marcos a year ago, today/They probably would’ve put me in a home”. The audience whoops. Johnston gives the camera a knowing look, and then smiles out at the crowd.