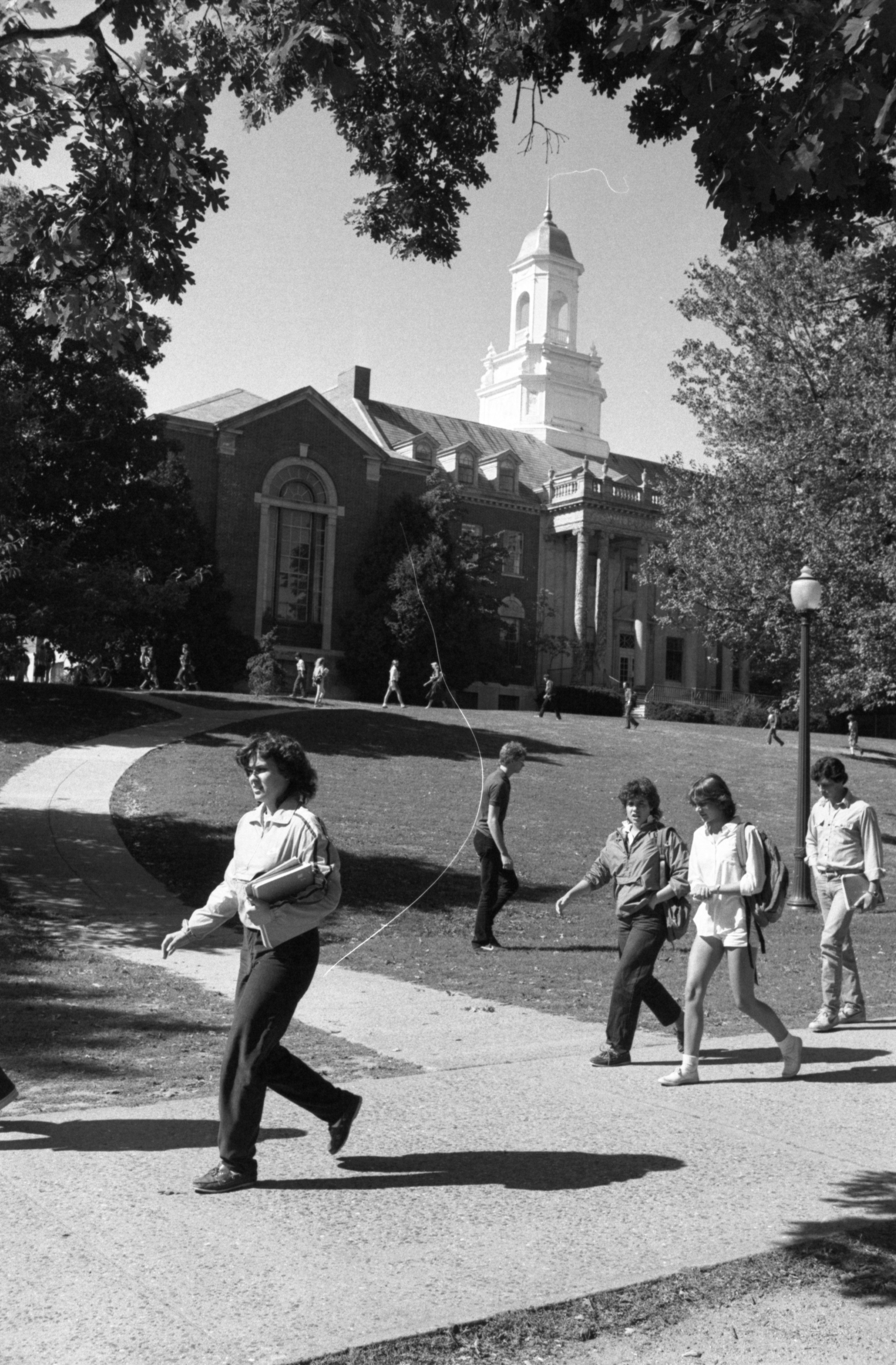

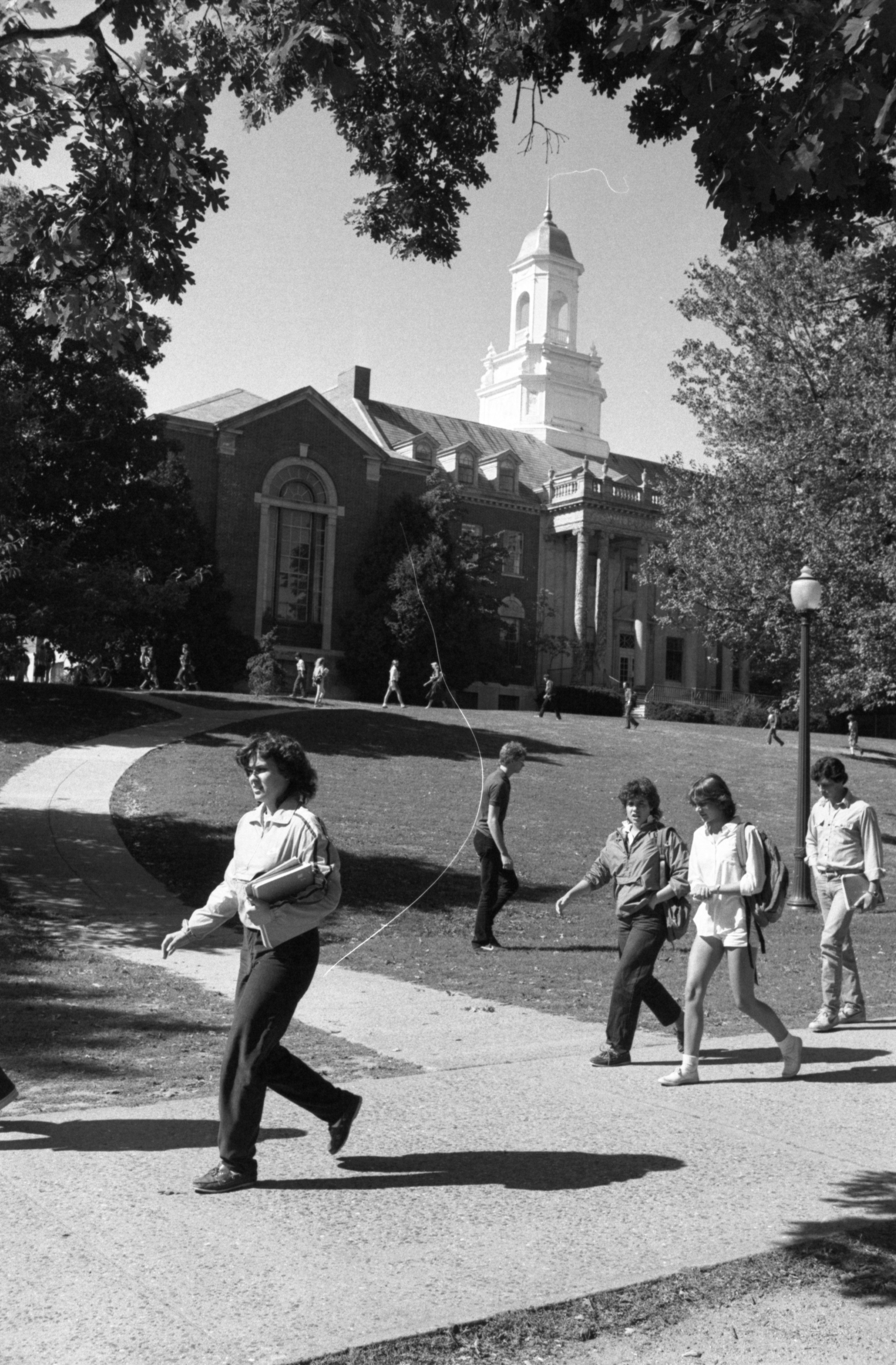

A picture shows a familiar scene on UConn’s campus: crowds of students milling about by Wilbur Cross Library. Friends chatting. Backpacks slung across shoulders. The only thing that differentiates this from any other day is the feathered hair and dated clothes.

This photograph is dated Sept. 29, 1983, and is entitled “Campus Views.” It can be found in the UConn Archives and Special collections digital archive and it’s one of many historical materials available from this campus resource.

The UConn Archives and Special Collections are housed inside the Dodd Center for Human Rights and provide a space for students, as well as the public, to conduct research or find out more about their personal interests by accessing primary source materials such as photographs, past UConn yearbooks and student publications.

According to Melissa Watterworth Batt, an archivist who oversees the collection of papers from Connecticut poets and writers, primary source materials could include something like a recording of an interview with a specific politician. This differs from the main library which mostly holds secondary sources such as books that critically analyze primary sources.

“A lot of students are interested in knowing the history of student life,” she said.

The Archives have an expansive collection documenting campus life which not only includes student papers and student honors theses, but also scrapbooks and materials from student organizations going back to the founding of UConn in 1881 said Watterworth Batt.

She also mentioned that the Archives house collections students might find surprising. These include a large collection of children’s literature, early jazz and blues records and even the old husky mascot costumes.

Last spring, the archive began assembling a new collection documenting the student protests for free Palestine. These include signs, ephemera and correspondence.

“During periods of war and periods of political upheaval, our collections are really a way for students to see a more nuanced and more diverse understanding about how that event happened or was influenced by people who lived at the time,” said Watterworth Batt.

Graham Stinnett, an archivist who oversees human rights and alternative press materials, said that while the archive is mostly used for scholarly research, people utilize it for all sorts of projects.

“A lot of folks who don’t have backgrounds in academia come to the archives to study old texts, or artists come to the collections that I oversee to look at old font of 1960s bumper stickers, political slogans, or things that the radical underground or counterculture has fashioned as an aesthetic,” he said.

Stinnett hosts d’archive, a podcast started in 2017 on WHUS radio, in which he plays some of the recorded archive materials and conducts interviews with experts and those with first-hand knowledge of historical moments.

“I thought it would be a great opportunity to air some of our recorded collections through the radio,” he said. “I could then expand the reach of archive to sort of unexpected spaces.”

Stinnett said that as the show progressed, he started branching out to more specific topics that could be enhanced with recorded interviews.

“Some of my favorite interviews have been with people who haven’t told a particular story about a collection that we have that maybe you wouldn’t get face value by just reading the documents that we’ve got,” he said. “They sort of add this color to it.”

One episode of his show featured Norman Stevens, the assistant director of the UConn Library during the 1974 Black Student Sit-In.

Stinnett put together an exhibition last spring with pictures of protesters being arrested, letters written to staff involved in the sit-in and the demands made by students to UConn administration.

In addition to providing primary source materials, the Archives also offer classes to students and the surrounding Storrs community ranging from art history to political science.

There are also many job opportunities for undergraduate students who might want to get involved.

“We have dozens and dozens of students who have gotten experience working here,” said Watterworth Batt. “You can learn anything from public service to how to re-house photographs.

Patrick Boots, a journalism student who often utilizes the Archives, said that both the physical and digitized versions have been very helpful for both his news stories as well as personal inquiries into UConn’s past.

According to Boots, it was weird to see the UConn campus in old photographs without all the modern-day construction.

“If we don’t work to record our history, we might forget it,” he said.