It seems as if terrorist attacks are happening more frequently than ever around the globe, and they have caused one Muslim-American student to continuously check the news, immediately hoping perpetrators are not of his religion.

“[During] any major event or attack that may happen, you’re thinking ‘I hope that guy isn’t Muslim,” he says. “That’s always the first thought of any major attack that’s on the news or headlines, because then there will be another wave of hate – Islamophobia.”

Shafi Khan, a sixth-semester Allied Health Sciences major at the University of Connecticut, says it is “worrisome” waiting to find out an attacker’s identity, as it often takes a day or two to confirm such information.

Khan says he has also been affected in other ways by negative perceptions of Muslims.

He was planning to go to Europe this summer, but his parents, who are from Pakistan, are concerned about growing Islamophobia and do not want him to travel. For Muslims, he explained, the travel bans of President Donald J. Trump’s administration have created dilemmas.

“Honestly, it’s almost unpredictable. He could sign an executive order the next day that says no Muslims are allowed in the country,” he says. “Of course, it could be overturned and all, but it’s kind of scary how much of an impact he has.”

Shafi Khan serves as the the Marketing Chair for the UConn Muslim Student Association. Photo: Darden Livesay

The Trump administration’s policies coupled with a surge of Islamophobia have incited reactions in the local Muslim community that range from feelings of fear and uncertainty to optimism and proactiveness.

Multiple members of the UConn Muslim Student Association say that the president’s rhetoric has increased anti-Islamic sentiment in the United States, breeding intolerance and misunderstanding both on campus and throughout the country.

Whether students or not, other Muslims have also encountered circumstances similar to Khan’s.

The founder of Houston-based DC Seminary, an institute focused on spiritually empowering Muslim professionals, graduates, and undergraduates, Fahad Tasleem says he and others had planned to travel for this year’s hajj – the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Even though Saudi Arabia was not affected by Trump’s travel ban, Tasleem says a lot of people cancelled due to fear of being barred from reentering the U.S.

In another instance, he recently adopted a girl from Morocco and had to travel and stay there for a month. Although Morocco was also not included in the ban, Tasleem says his family and friends still worried about whether he would be allowed to return to the States.

“It’s really hampered a lot of people’s ability to travel. It’s their own fear,” he says. “That climate of fear is something that I’ve really sensed a lot within my own family, within the Muslim community, and so on and so forth.”

Fahad Tasleem gives a guest lecture at the UConn MSA annual Spring Dawah Dinner, March 23 in the Student Union Ballroom. He primarily discusses the philosophy behind religion, especially in relation to Islam. Photo: Darden Livesay

The executive order also affected couples, at times keeping loved ones an ocean’s width apart.

Bassil Akkach, a tenth-semester student from Syria studying Allied Health Sciences, says Trump’s order temporarily prevented his cousin Alaa from bringing his Syrian wife to the U.S. from Jordan. He added that even though Alaa is an American citizen, and his spouse obtained a visa the day before the ban, she could not come until two weeks after it was lifted.

Akkach, who is also an American citizen, says he was not individually affected by the policy, but many others have not been as fortunate.

“It’s gotten even irrational and it kind of affected a lot of people who work here and build their lives here,” he says. “They may not have a citizenship, but they’re still people who own property, they’re students in universities, or they have businesses. There’s a lot of diverse people who’ve been affected by this ban, basically – doctors, engineers and other people.”

According to the Pew Research Center, 59% of Americans disapproved (compared to 38% who approved) of Trump’s policy to stop refugees from entering the U.S. for 120 days and to prevent people from seven majority-Muslim countries from entering on a visa for 90 days.

Other MSA members described travel difficulties that Muslims have endured recently in airports.

Vice President and sixth-semester mechanical engineering major Fahim Ibrahim, whose family is from Bangladesh, recalled how he received unequal treatment from airport security last winter. At the time, he was traveling to Bangladesh and had to stop in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, where he was selected and put in a room for two hours to wait while officials checked his baggage.

“It was kind of out of the blue, because I had an American passport,” Ibrahim says. “I felt like just by my last name they kind of randomly selected me and just wanted to look through my stuff a little extra.”

He added that there were other “brown people” in the room with him too, but he just referred to it as “typical stuff that goes on.”

“They treat the Bengalis or the Muslim people way differently than the people who look more American. Even though we had American passports, they would still treat us differently” – Fahim Ibrahim on Abu Dhabi airport officials. Photo: Darden Livesay

In the U.S., the Transportation Security Administration inconveniences Muslims in general, according to MSA President Sana Suhail; however, she says that since the bans they have been interrogated even more.

Suhail told a story about airport security agents in March detaining one of her friends for 16 hours, taking her passport and making her wait in line for questioning before being allowed to travel from the U.S. to Israel.

The travel ban, Suhail says, mostly affected everyday travelers rather than catching someone who poses a legitimate threat.

“I just think that it’s creating unnecessary hysteria and unnecessarily exacerbating Islamophobia in general,” she says.

The hysteria is apparently not limited to just the U.S.

Professor Reda Ammar, the MSA faculty advisor and director of the Islamic Center at UConn, says there is now a phobia in Arab countries’ airports because of an obligation to uphold U.S. interests.

During the March 2016 terrorist attack in Brussels, Belgium, Ammar was at the airport in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. After telling a security official about his artificial knee, he was sent for inspection but repeatedly failed. Subsequently, an inspector began prodding into the knee.

“He started trying to find something inside,” Ammar says. “I was laughing, ‘What are you doing? Look at this [knee], this [surgery] was done 3 years ago. Do you think I bought a bomb for 3 years?’”

Another everyday traveler who has been impacted by tighter restrictions is MSA Event Coordinator Nur Ellafi, who says that having Libya as the place of birth on her passport makes traveling more difficult despite being an American citizen.

An eighth-semester physiology and neurobiology major, Ellafi says it is most challenging when family members try to visit her and vice-versa. She also says her mother was recently traveling from the U.S. to Palestine when she was held up in customs, berated and mistreated by a TSA agent.

“We’re always weary because, whether or not you’re a U.S. citizen, Islamophobia still affects you, especially when you’re from targeted countries,” she says.

Ellafi, who came to the U.S. from Libya in 2001, says the Trump administration has made it more acceptable to hate Muslims.

“When you walk through campus, there seems to be a kind of pride or uproar within people who are Islamophobic as well as xenophobic in general,” she says.

Ellafi cited an example from the MSA Spring Dawah Dinner in March, where an unknown individual outside of the Student Union Ballroom abruptly yelled “F— terrorism” during Tasleem’s guest lecture.

The hatred is not necessarily confined to words, as some Muslims have been physically attacked on rare occasions.

Akkach says he has friends who have been publicly harassed since the election in his hometown of Fairfield, Connecticut. One of his friends was pushed by a stranger in a mall, and another had her hijab pulled off by someone in a supermarket.

“That’s starting to happen around the country; it’s not the only incident, but these are two things that happened where I live, and we’re talking about Connecticut, which is considered a liberal and a Democratic state…” he says. “There is a rise in Islamophobia in this country because of this election.”

Because of Islamophobia, Muslims may feel uncomfortable demonstrating their faith in public, even if they are not faced with outright animosity.

Arab Student Association President Ahmed Ouda, whose parents are from Egypt, says he feels scared if his mother goes somewhere like Times Square in New York City where there is exposure to large crowds of people.

“I think especially Muslim women face a lot [of discrimination] because they have an external expression of their faith with the scarf,” the eighth-semester finance and economics double major says. “It’s tough.”

Ibrahim says that social interactions with non-Muslims on campus are different for females with hijabs or males with long beards.

“It’s kind of always in the back of your head, ‘What does this person think of me? What do they see me as?’” he says. “Besides me being a human being, what do they think of me being a Muslim?”

MSA students gather in the Student Union Ballroom for Maghrib prayer, the fourth of five prayers performed daily by practicing Muslims. Photo: Darden Livesay

For Muslims, concerns that others perceive them negatively often stem from the fear of being misunderstood by outsiders.

Suhail says a major reason for misconceptions about Islam is the news coverage that constantly associates it with violent imagery, despite the fact that one of the religion’s major tenants is peace.

“The Muslims in the world look at that imagery and they see it as the media portraying all of them in that light, even though that’s so far from the truth,” she says.

The so-called Islamic State has been designated a terrorist organization by the United Nations and many countries. The radical Islamist militant group is widely known for its videos of beheadings and its destruction of cultural heritage sites. The group claimed responsibility for the shooting death of French police officer Xavier Jugelé in Paris two weeks ago.

Photo: Flickr/Day Donaldson

Akkach says people must understand that moderate Muslims living in the Middle East are the primary victims in any terrorist attack.

“What they see going on in the Western countries is nothing compared to what Muslims see in their daily lives back in Middle Eastern countries…” he says. “They always see this terrorism happening to them. They’re the ones who are always losing family members. They’re the ones who being denied of education and their basic necessities of life because of that.”

Militants from the IS control 23,300 square miles of Syrian territory as of Dec. 2016, according to the Information Handling Services Conflict Monitor; however, an Al-Jazeera map from March indicates that the jihadists have been losing ground in the past few months.

Nonetheless, Akkach says he feels “humiliated” that the Islamist terror group controls so much territory in his home country, and that the situation even prevented one of his friends from visiting his terminally ill father in the hospital before he died.

In order to counteract stereotypes about Islam being a radical and violent religion, Muslims of the local community emphasized engagement with others and sharing of information.

Ibrahim says they have to reassure themselves that people perceive them in a positive manner while actively raising awareness about their faith.

“If you always put yourself down as a Muslim that they’re always against us, you’ll never get anything done,” he says. “Our best interest is to serve the community before we serve ourselves, to make sure that everyone knows that we’re on their side.”

Suhail says there is a lot of work to be done and that Muslims cannot simply expect the general public to think the best of or know everything about them.

“We need to put ourselves out there, introduce ourselves as Muslims and talk to people about the kind of lifestyle that we live and how totally different it is from what they may have been thinking,” she says.

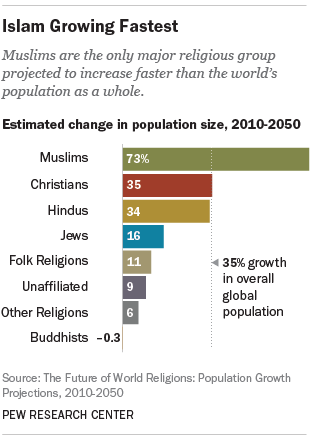

There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010. Islam is the world’s second-largest religion to Christianity, but it is the fastest-growing major religion. Credit: Pew Research Center

With regards to the future, MSA members and affiliates offered more advice and opinions that seemed to lean in a positive direction.

Akkach says that, whether people like it or not, Muslim-Americans have important roles in the U.S.

“There are Muslims as doctors, as engineers, as soldiers fighting with the country,” he says. “We are part of the American society, and that’s something they have to understand very well.”

More Muslim-American politicians are what Ammar expects to see, and he hopes they can evoke constructive change.

“These politicians need to sit down and find a way to protect the country without bothering the citizen, at least the citizen and without [there] being any discrimination…” he says. “I’m sure there are hundreds of solutions.”

Tasleem revealed that, despite concerns among Muslim-Americans, his outlook for the future remains positive provided that Muslims present the best image of Islam and follow its principles, such as being kind to neighbors and the elderly and feeding the poor.

“I think when things like this happen, it’s kind of like God kind of shaking us up and saying, ‘You know what? It’s time to wake up,’” he says. “Both for Muslims and non-Muslims.”

[An MSA student chants the Maghrib prayer]