Though he’s the age of a typical college sophomore, Divine “Bam” Durant, 19, lives a life common to most young, black men. He’s smart, but he’s not in college. The streets are his professors. His classroom is where he lives, Red Hook Houses, the largest public housing project in Brooklyn.

Though Durant wanted to finish high school, circumstances made that difficult. Commuting to school from his girlfriend’s or a relative’s apartment was a lot to handle. Instead, pressures in his community and at home sent him on a different route. He left school to take a job, which forced him to grow up quickly.

Dreams are hard to hold onto in Red Hook Houses. He imagines the world is much bigger than Red Hook. He invites us in.

This is Red Hook.

A winter storm left many obstacles for the resident of Red Hook Houses, but none as substantial as the ones they face every day. The community is home to families, single mothers, dope dealers, lone men and children. This is a place where history repeats itself, and it’s rarely good. For a young person, sometimes joining a gang seems like the only way out. Sometimes the only way out is to leave the only home you’ve ever known.

Red Hook Houses was built in 1939, as part of a federal work and housing initiative under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. With the Great Depression ending, it promised modern housing for families at a reasonable cost, but it hasn’t fulfilled that promise for decades. Today it is one of the largest public housing projects in the country, with more than 8,000 predominantly black and Hispanic residents. According to the New York City Housing Authority, the average gross income of people living in public housing is about $23,000. The New York Daily News reports crime increased 65.2 percent from 2009 to 2013.

Red Hook Houses was built in 1939, as part of a federal work and housing initiative under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. With the Great Depression ending, it promised modern housing for families at a reasonable cost, but it hasn’t fulfilled that promise for decades. Today it is one of the largest public housing projects in the country, with more than 8,000 predominantly black and Hispanic residents. According to the New York City Housing Authority, the average gross income of people living in public housing is about $23,000. The New York Daily News reports crime increased 65.2 percent from 2009 to 2013.

“I don’t want to be just another statistic” – Divine Durant.

“I don’t want to be just another statistic” – Divine Durant.

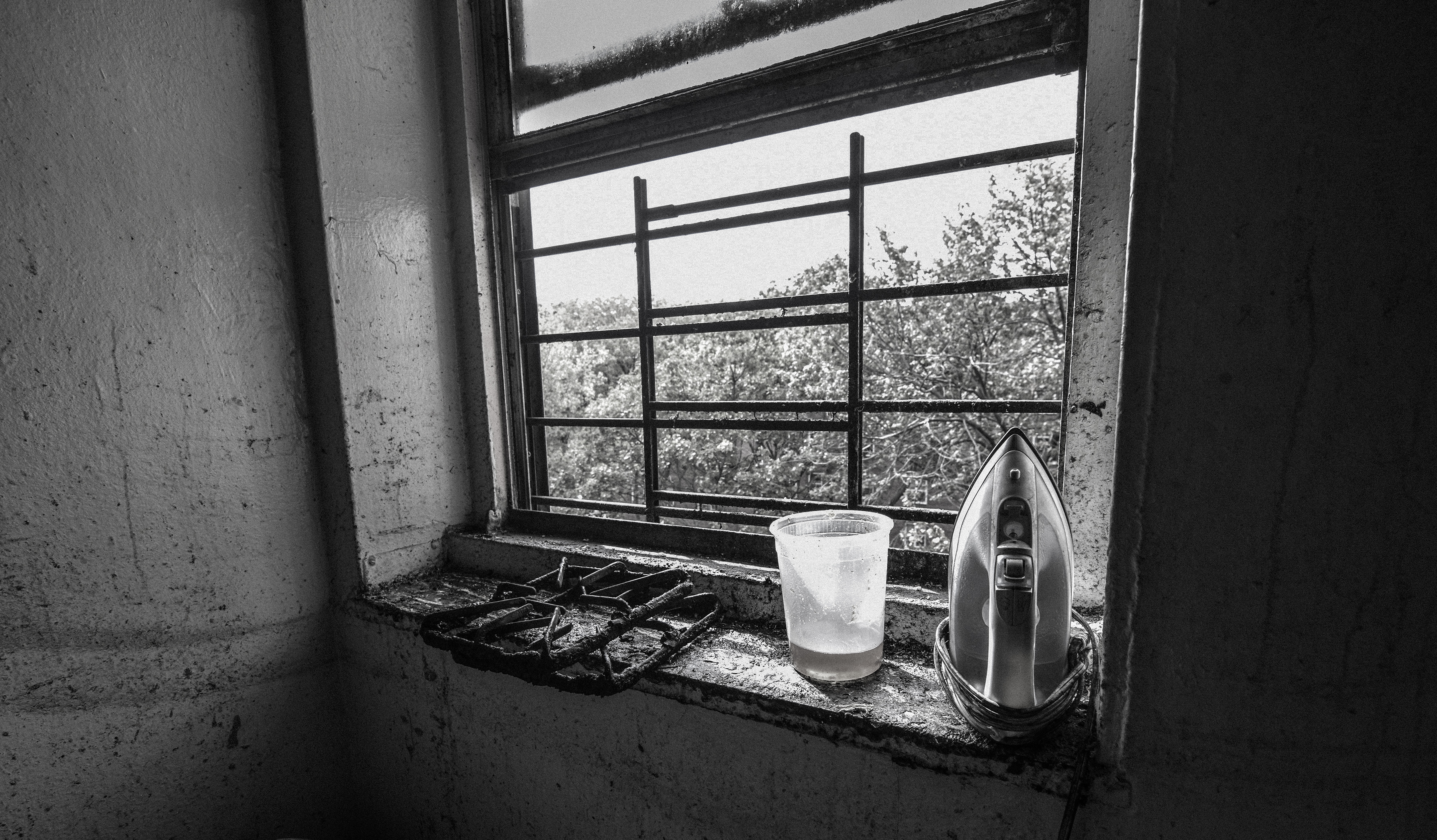

A security camera watches from above as Durant rides to the fifth floor of his building. He lives on the sixth floor, but the elevator doesn’t go that far. He has learned to step around the trash and puddles of urine in the elevator and stairwell. The roaches and rodents just scurry out of the way. Durant said it’s not so bad, “At least I’m alive.”

“Just because we smoke weed doesn’t mean we’re bad people.”

“Just because we smoke weed doesn’t mean we’re bad people.”

Durant relaxes with friends in his bedroom. Unlike his friends, Durant dropped out of high school in his freshman year and got a job. He’d like to get his GED eventually, he says, but he has no immediate plans. “School isn’t for everyone,” he says. Right now, he and his friends just need to unwind and make plans for the evening. For many, marijuana is a way to relax. “My mother is mad I smoke but she knows it’s copacetic for me,” he says. “Instead of being outside and in trouble, you’re inside smoking a joint, not bothering anyone.” Going out isn’t safe, but staying in is boring. They decide to go out.

“They don’t care about us”

Living in Red Hook Houses means everyday struggles. Paint is peeling from the kitchen walls of the apartment Durant shares with his mother and five other relatives. A neighbor complains that her bathtub gets clogged with water from the apartment upstairs. Last year, Durant’s mother slipped in a puddle of urine in a stairwell and fell down a flight of stairs. She pays more than $1,500 a month for their three-bedroom apartment.

Durant waits at a bus stop with his mother, Chrystal Durant, to see her off on her way to work. Her shift starts at 11 p.m. She works six days a week at the Metro North 4th Avenue train station. Some nights she asks him or his brother to walk her to the bus stop, but tonight is different. She says she’ll be fine and pleads with him to go home and “get off the streets.” Durant says he and his mother went through rough times, but things are better now. “It’s not exactly what I want, but it’s perfect for the time being,” he says. “I can’t talk to her about everything and ask for much, but I have to accept what is given.” After hearing sirens while on the bus, his mother calls to make sure that he got home safely.

“The use of weed isn’t killing us; it’s the people selling it.”

“The use of weed isn’t killing us; it’s the people selling it.”

Many of the crimes in Red Hook are drug related, and marijuana is common. In the past, he says, “I could never see myself smoking weed, but it made me calmer when I was in that dark place.” The penalty for marijuana possession varies depending on the amount and whether there is an intent to sell. “You can lose your whole life for weed,” he says.

Police drive by curious residents after arresting a man on suspicion of selling drugs. Durant says it’s not smart to stand and watch such things. “You never know what the situation is,” he says. “They turn and look for anyone. You could be just standing near a scene and they’ll harass and disrespect you as if you’re involved.” As a young black person, he feels particularly vulnerable. “They just see the color of our skin. We’re just those black kids. They don’t care about our names.”

“People think they have to act a certain way because they’re from the hood but we can change that dynamic”

“People think they have to act a certain way because they’re from the hood but we can change that dynamic”

Gang violence and drugs have created a mindset among young people in the neighborhood, Durant says. “They feel like life is short because they’ve grown up in the hood. They think they have to fill a certain image.” One of the reasons he left school, he says, was because of the fights. “I used to get chased by kids in other projects. No one knew what they were fighting for.” He plans to leave Red Hook. He dreams of becoming a clothing designer. He and his girlfriend are working on a website that will showcase his designs, and perhaps be his ticket out.

I blame my father for his death. No one just dies. You knew you could’ve stopped it as an adult.

Durant’s father died a couple of weeks before he was born. As he understands it, his father was shot when he refused to allow another drug dealer to sell on his turf. His father should have gotten out of the drug business when he had kids, he says. “It’s extremely hard” to grow up without a father. His mother, a single parent, was busy raising him and his five siblings. He says he had to learn how to be a man on his own. “I am who I am because I have to be, and no one can change that,” he says.

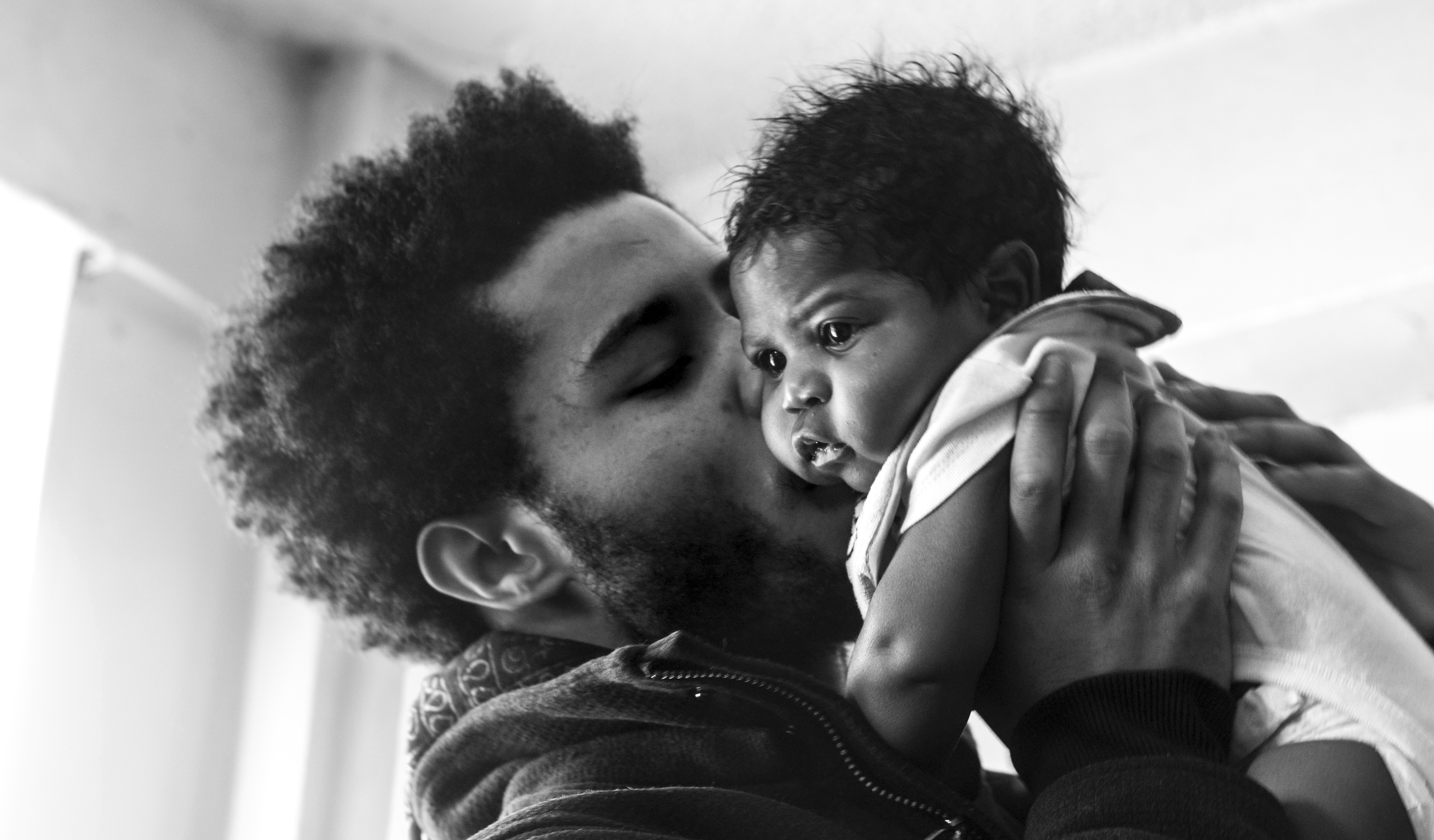

“I want you to have a better life than me.”

Durant and his nephew share a moment before he leaves to meet with friends. For Durant, who is the youngest of his mother’s children, he wants the best for his younger relatives, especially the males.

Even though you are hurt and intense, find a purpose

Even though you are hurt and intense, find a purpose

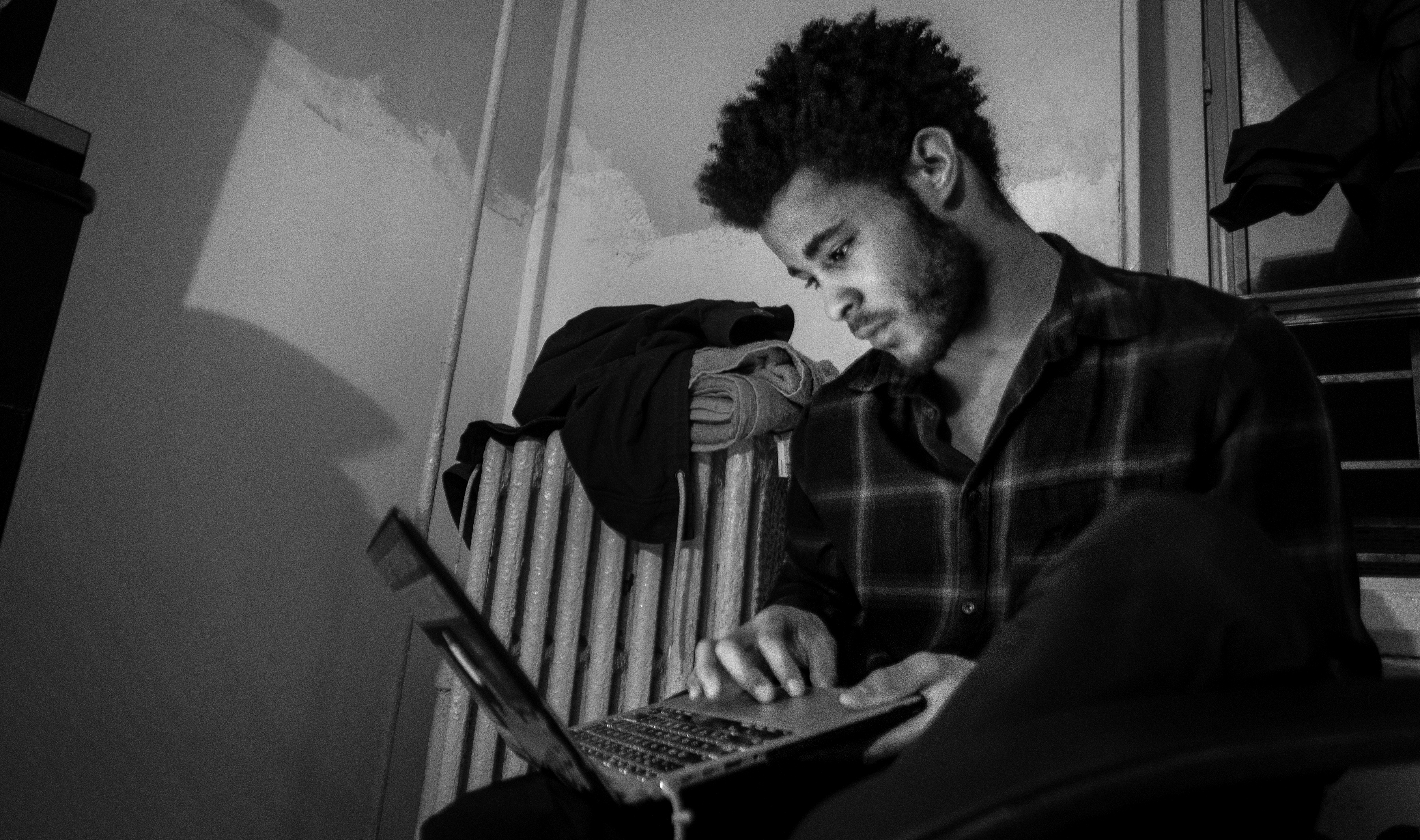

Durant is trying to save money to pay for his own clothing line, which he wants to launch online before his 20th birthday, just three months away. He began designing clothes shortly after dropping out of school. At first, he would just adapt store-bought clothes to give them his own look. Then he taught himself to sew and found a passion for creating original pieces. When he is successful, he wants to give back to the community, and he wants to write a book, he says. “Find something to put that anger to. Don’t give up because the government wants us to. Don’t compromise for anything less.”

Stay updated with more visuals of the story and gallery dates by emailing Alyssa.hughes@uconn.edu