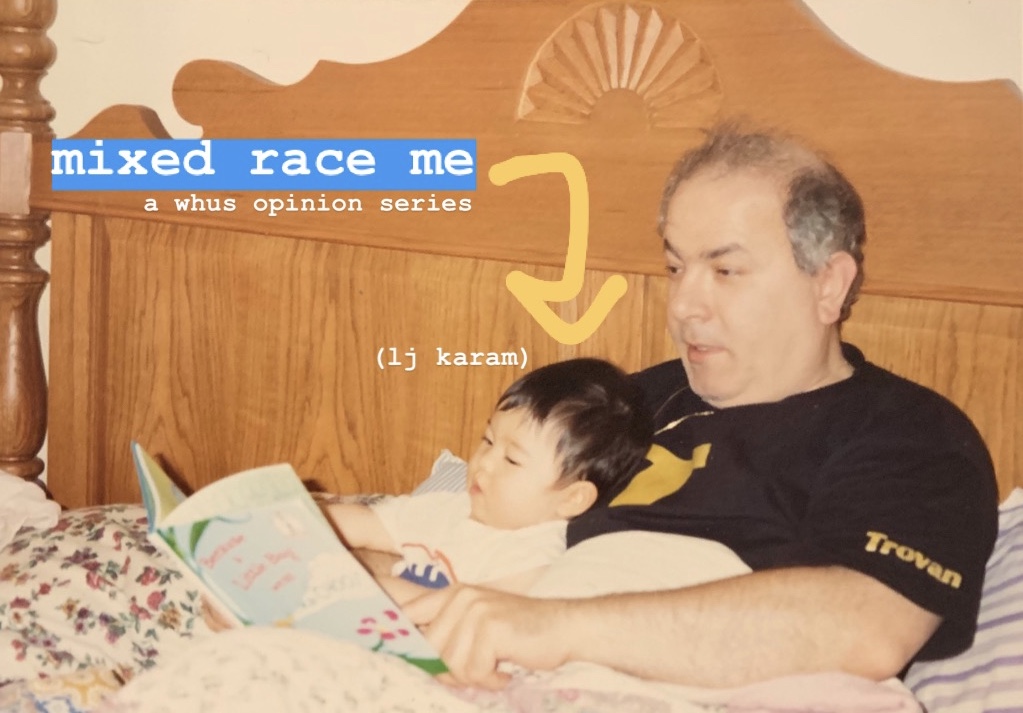

I was 19 years old when I found out that it wasn’t the norm to carry your birth certificate with you during international travel. My father always has mine on-hand when we go on trips to Lebanon to visit our family.

He carries it with us in the case airport security flags him for human trafficking. It has already happened before.

Though my passport carries our last name, my face does not show it. I have most of my mother’s physical features, and this is the reason that airport security would rather believe I have been kidnapped than believe that I am my father’s child.

When my mother gave me her face, she laid claim to how the world would see my identity. I might not look all that Chinese, but I look Chinese enough for nobody to ever believe I was Lebanese unless I could prove it to them.

I’m never asked about my identity as an Arab American, and I’m never asked about my father’s immigration story. Since he is my “white half,” he is ignored.

Those of homogenous racial or ethnic backgrounds are always asked about their parents. Plural. Both of them. I am only ever asked about my mother, because she is who people see when they look at me.

She is the non-white parent, so therefore she must be the source of all my great ethnic superpowers.

The line of questioning is fairly standard. They want to know about where she’s from (Brooklyn), when she came to the United States (she was born in Brooklyn), and what I mean when I say that her “accent is so thick” (she’s from Brooklyn).

If only they would ever ask about my father.

George Karam came to the United States in 1983 from Beirut. He left during the Lebanese Civil War, like most of the diaspora. He did not become an American citizen until after I was born. English is not his first language. It isn’t his second language, either. He is more highly-educated than any college professor I have ever had.

When people look at me, I want them to see my father too. The parts of myself that I am the most proud of are the parts that remind me of him.

If you wonder where I get my near-unhealthy obsession for school and learning, it’s because I see him in all of my teachers.

If you want to know why I’m so passionate about reading and why I advocate for literacy so much, it’s because I can still hear his voice reading Curious George Goes to the Hospital while I turn the pages.

And if you ever wonder why I refuse to compromise my work ethic, it is because everything I do is for him. Because everything he has done is for me.

So you must understand how it feels in the pit of my stomach when someone does not believe that I am his daughter. That terrible feeling has compounded for 21 years, and it will compound for the rest of my life.

Is it really so difficult to ask for a suspension of disbelief in order to entertain the concept that a person can be more than one thing? That I can be both Chinese and Lebanese, and maybe American too? That I can be my father’s and my mother’s at the same time?

It is so exhausting to have to constantly correct people who have their own theories about how my father and I are related. Sometimes I wonder if I should just let them stare. Should I let them poke and prod at me like I’m part of a zoo exhibit?

Maybe it would be easier if I could agree with them, and tell them I understand where you’re coming from. That I can see how they’d assume I was adopted, or a mail-order bride, or the nanny. That would be easier, right?

No.

Things that are not morally right to me have never seemed easier. I refuse to lend credence to ignorance out of exhaustion for the same reason that I would much rather fail outright than ever cheat on a test.

I get it from my dad.

I am more proud of my father than I am of anyone else in this world. Nobody means more to me, and I am confident that nobody ever will.

It is offensive to term me as “half” of any part of him when you would never do the same to someone who is of a singular race or ethnicity.

The language used to refer to mixed race people traps them in a space obsessed with strict categorization that sees them as either “half-this” or “half-that.” This attention to the half means that my claim to my identity is illegitimate because I lack the fullness necessary to stake one in the first place. Attention to the half means that I am never allowed to be whole.

Manipulating my appearance into being the sole representative for my cultural identity does a great disservice to the storied and unique ethnic background I hold so dear to me.

The assumption that one parent could be more impactful than the other simply because they share more of a physical resemblance to their child is egregious and abhorrent.

For it is one thing to look at me, but it is another to see me.

This is for you, Baba. I want them to see you too.